I continue my travel across various encyclopedias' entries. This time I visited the Open Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science and its entry on Compositionality:

Nefdt, R. M., & Potts, C. (2024). Compositionality. In M. C. Frank & A. Majid (Eds.), Open Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science. MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.21428/e2759450.494deacd

"Compositionality is a central concept in cognitive science, with applications in linguistic, visual, and general cognition. In studies on language, the principle says that the meaning of a syntactically complex phrase is a function of the meanings of its constituent parts and the way they are combined. One can think of this as specifying a recursive process in which lexical items (e.g., words ) have atomic meanings, and these come together to form phrasal meanings (e.g., noun phrase), which are themselves inputs to more complex phrase meanings (e.g., sentences), and so forth. The principle can be seen as offering an explanation of why and how people are able to produce and interpret novel well-formed expressions: the meanings of such expressions are taken to be fully determined by their syntax and the lexical items they contain."

Even the usual use of language creates lots of problems for this principle. For example, how do we determine the "atomic meaning" of a polysemous word in a given noun phrase? Or, how can the same noun phrase mean different things in different contexts? And my favorite, what is the "meaning" of a noun phrase taken abstractly and applied to a certain context?

But there is an additional layer to the language use - allegories, metaphors, idioms, etc. The word "kick" and the word "bucket" have their "atomic meanings" but I fail to find their traces in the meaning of the phrase "kick the bucket". Does this "mean" that I do not "understand" recursion?

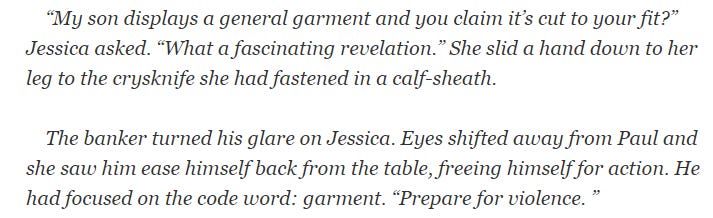

Now consider my favorite example, code words. The following fragment is from Dune by Frank Herbert.

What makes the banker understand that phrase differently from Paul? Do you see how easy it is to assign not just a new meaning to a word but even a new way of interpreting a sentence?

Consider the following example. A mother tells her husband in private "When you are back, mention a butterfly in a positive or negative sentence and I will understand whether you bought a present for our daughter's birthday." The father comes home in the evening and says "I saw a big and beautiful butterfly today." The daughter reacts with "I also saw a butterfly today." How will the mother understand those two almost identical utterances? This example illustrates the power of words’ referential flexibility. Just like the "garment" example. This example may illustrate one more opportunity. Consider the father answering "I haven't seen a single butterfly today" and the mother asking him "Have you been in the park?" I claim that additional convention about the "park" is not necessary.

Pay attention to the term "referential flexibility". I coined it to address the ease of assigning new meanings. However, the cost of spreading this new "assignment" is proportional to the size of communities. This explains why small groups are much more agile in coming up with novel jargon. Another issue worth mentioning here is the test of time - some assignments may prove to be inconvenient if they create more ambiguities than value in communicating new meanings.

"the modern form of the principle is due to Richard Montague. One of Montague’s central tenets was that there is “no important theoretical difference between natural languages and the artificial languages of logicians”."

Surely, Montague saw "no important theoretical difference between" "kick the ball" and "kick the bucket". I agree that there is a place for logic in natural languages but I claim that there is more to natural languages than logic.

"At its core, the principle of compositionality is a mereological process that breaks complex structures into meaningful constituents or parts. For example, the sentence “the kitten sleeps quietly” contains two phrases, a noun phrase (the kitten) and a verb phrase (sleeps quietly), that come together to form a sentence: [[the kitten] [sleeps quietly]]. The meanings of the lexical items are stipulated. The meaning of the subject “the kitten”—call it α—is determined by a function applied to the meanings of “the” and “kitten.” The same logic applies to “sleeps quietly” to produce a meaning β, and the meaning of the entire structure is then determined by a function applied to α and β."

I like the idea that the "meaning" of a word or phrase is what the word or phrase "stands for". Even if we ignore for now polysemy, there are two options here that I consider important to differentiate. Consider the phrase "red dog". It can be considered abstractly or in context.

Before we proceed I propose to clarify the role of language. Ev Fedorenko et al. in the 2024 paper "Language is primarily a tool for communication rather than thought" provide evidence in favor of communication. I agree but find it necessary to clarify that communication is a two-stage process. Language is involved in the first stage, which guides the attention of readers or listeners to the relevant phenomena in a given context. During the second stage, the cognitive modules of readers or listeners perform the heavy lifting of collecting all the available information about the relevant phenomena. Therefore, language does not have to "encode" all the information because perception/memory/imagination process information better.

The phrase "guiding attention" means that language is essentially a pointing finger with advanced capabilities. It can point not only at the objects and actions but most importantly at facts, which connect objects and actions. Now we are ready to find the "red dog" in the following picture "showing its tongue".

We can focus on many items in that picture, for example, on what looks like a dandelion leaf. But I want you to focus on a dog. So, you no longer are looking at the leaf but there are for dogs. Please focus on the red one. Note that "the red dog" is not completely or even mostly red but it is the only dog with something red about it. Montague would find my claim that it is "a red dog" logically false. However, I am fine with that phrase because it is sufficient to identify the relevant dog. Note that I could use other terms - Animal, Border Collie. I could use other additional information - "third from the left". What is important is not to use information that does not help in the differentiating process - "showing its tongue", "sitting", "staring", etc.

Pointing works like a search light, language works like a filter. The first filter "dog" filters out "dandelion leaf", "grass", "background", etc. The next level filter "red" filters out the other dogs. The initial set of objects in the context of this picture has been narrowed down to a single object. Mission accomplished!

Now forget the picture. And think about "red dog". In a different context, it may be (and most likely will be) a totally different object. It may be that the context will contain several fitting candidates or none at all. The former case will require additional filters, the latter case will require dropping or relaxing the existing ones.

Abstractly, any phrase is only a filter. "Meaning" is what it leaves you with when everything else has been filtered out.

Now back to "the kitten". The word "kitten" is the content word. It applies directly to the context. The word "the" is different. It belongs to the domain of auxiliary words responsible for addressing other "pointing/filtering" needs. Grammar as a whole is responsible for facts. The sentence "the red dog shows its tongue" connects the dog with the action and the object of that action. Grammatical constructions are differentiated according to rules that are different from those for differentiating the relevant objects in the context. Hence, it's not so simple to deal with "the kitten".

"Compositionality itself does not dictate what the parts are. The example assumes that “sleeps” and “quietly” were atomic units, but they could be decomposed into smaller meaningful (but perhaps more abstract) parts, like “sleep” plus present tense and “quiet” plus an adverbial meaning. It is similarly possible to treat frozen expressions like “a lot of” as atomic units. The compositionality claim can thus be seen as conditional: if the syntactic analysis breaks an expression down into parts, then some compositional analysis of the parts must be correct."

If compositionality is conditional (nice pun) then it should "dictate what the parts are". Be it the parts of words like "-ly" in adverbs, words themselves, or "frozen expressions" or idioms like "kick the bucket". Without knowing how to decompose the whole correctly into parts of "atomic meaning" (one-level filter) it is hard to expect the correct interpretation of the whole.

"Theoretical arguments for compositionality have generally involved three distinct properties: productivity, infinity, and systematicity.

The argument for productivity relies on the fact that humans can produce countless sentences with a limited lexicon and memory storage. Thus, semantic theory needs to explain this capability in finite terms, and compositional systems are candidates for such explanations."

The world provides us with the infinite variety of unique objects that can be combined in yet bigger number of ways. Having a unique word for each object or combination is infeasible. Productivity is a result of the compromise between our limited memory and the need to address the infinite variety of the real world. In my previous post, I explained how concepts help with that. The post is here - Objective Concepts.

"The phenomenon of productivity is sometimes described in terms of human’s “infinite” capacity to use language. The sense in which this is an infinite capacity is highly idealized and depends on many assumptions about language and cognition, but the space of expressions people can use is so vast that it cannot possibly reduce to memorization, so the question of infinity can be set aside here."

An accurate description of the abovementioned "red dog" is possible but hardly necessary. The infinity of possible expressions is definitely overestimated but still large indeed. It is dictated not only by the vast number of possible situations out there but also by the fact that each speaker may take a different view on each situation.

"Finally, a related notion to compositionality is systematicity. This idea can be expressed in distributional terms: if (1) you know what “the kitten sleeps” means and (2) you know that “kitten” and “puppy” are related in relevant ways, then (3) you know what “the puppy sleeps” means. In a sense, 1 and 2 seem to fully determine 3. Compositionality can be seen as an explanation for this systematicity, but the observations alone do not entail compositionality."

I explain this by the need of efficiency. "Entities must not be multiplied beyond necessity." Only when we need to focus on a crucially different aspect of some phenomena do we introduce novel structures in language. And they have to be conventionalized by the community and pass the test of time.

"assume (at least for purposes of illustration) that “the kitten ate the treat” and “the treat was eaten by the kitten” are synonymous — call their shared meaning ɣ. Then no subsequent meaning operation can distinguish these two sentences. It follows, for example, that no compositional rule operating on this sentence meaning could depend on the identity of the subject of the sentence because the rule can see only ɣ. That is, because the rule can only see ɣ, it is insensitive as to whether the subject is “the kitten” or “the treat.”"

Language guides attention. When "the kitten ate the treat", our attention follows the kitten and we collect one set of information. When "the treat was eaten by the kitten", our attention follows the treat and we collect a different set of information. This aspect of "meaning" is seldom discussed by linguists. I think it should not be forgotten at least.

"There are a wide range of challenges to compositionality. One is the ubiquitous issue of ambiguity. For example, in “I saw a crane pick up a steel beam,” people tend to infer that “crane” refers to a machine rather than a bird because of the content of “pick up a steel beam.” Thus, the process of ambiguity resolution depends on the broader context."

Most words of any language are polysemous by necessity. Especially this applies to the most frequently used words. Apart from metaphorical usage, words are used in each phrase and context in one of its possible meanings. Therefore, compositionality is not broken here. However, we need to have the "polysemy resolution mechanism". Consider reading the "high key" example in the following post of mine for one possible approach - Symbolic Communication.

"A second issue is that of discourse-dependent items. In a discourse like “The kitten is sleeping quietly. She had a long day,” the pronoun “she” is very likely to be interpreted as referring to the same entity as “the kitten” in the first sentence. This looks like a highly nonlocal dependency — a reader or listener cannot resolve the meaning of even the entire sentence “She had a long day” in isolation."

A long time ago I wrote a post Reference Resolution for NLU where I described how to handle the famous "visiting relatives" example. Pronoun resolution is not much more difficult. The only thing we need is to track references to previously introduced entities. If a pronoun's "meaning" is resolved then there is no problem with proceeding further as compositionality prescribes.

***

My view on the principle of compositionality and on the whole NLP discipline is somewhat different from those widely accepted and practiced ones. You may say that considering references as filters discards compositionality. Or you may say that I "compose filters".

Whatever view you choose to take, consider using these ideas as additional building blocks from which to compose better theories of language.

Compositionality is a concept that is not related to practical tasks of language use. Therefore, it is not used in any way in relation to artificial programming languages, data representation languages, etc.